Have we had it all back to front? Ten years ago, a man known as the Berlin patient was cured of HIV. It was thought that a bone marrow transplant he received for cancer, from a person immune to HIV, had eradicated the virus from his body. But evidence from a new group of people suggests an immune reaction provoked by the transplant may actually have been responsible.

The cancer therapy is so harsh that it wouldn't be given to people who don't have that disease, but if confirmed, the finding gives us a new insight into how to fight HIV.

The Berlin patient —Timothy Brown— is still the only person who seems to have remained free from HIV for a long period. A few other people have been "functionally cured" —although they have some dormant virus in their cells, they no longer need to take antiviral therapy.

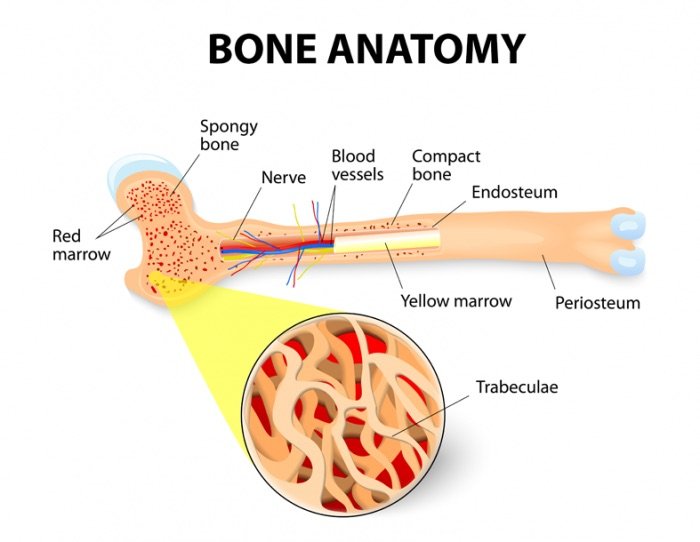

HIV targets immune cells, leaving people defenceless against other infections if it goes untreated. The standard view was that Brown was cured by a bone marrow transplant he received to treat his leukaemia.

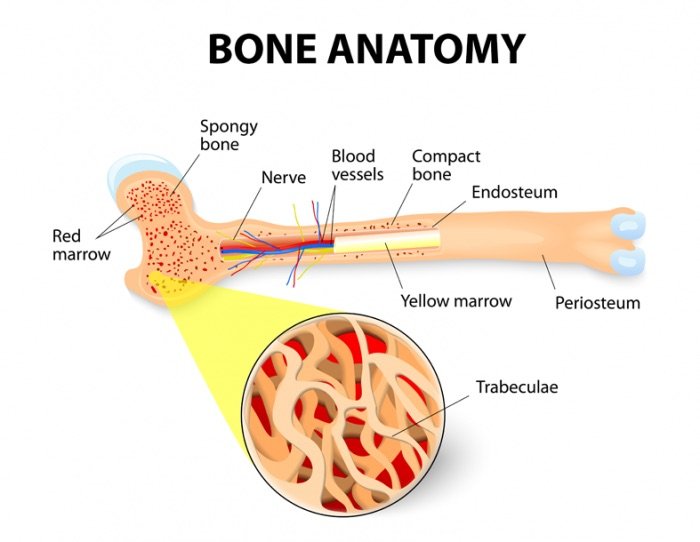

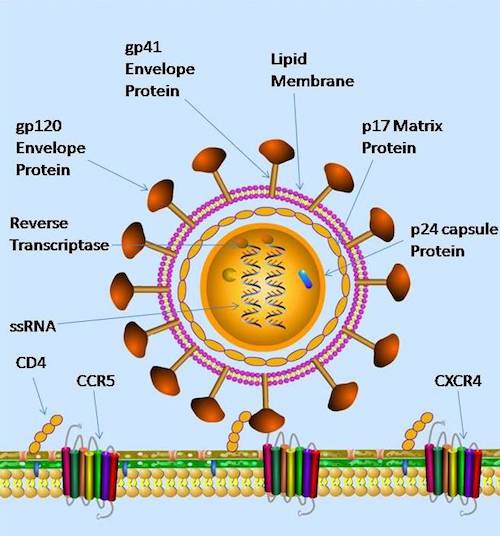

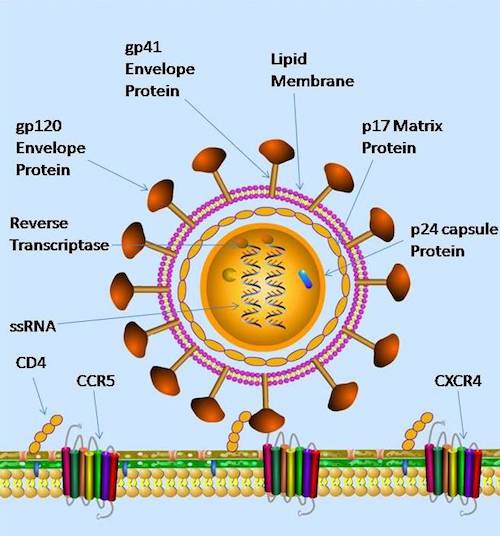

The bone marrow came from someone with a genetic mutation in the CCR5 gene that makes immune cells resistant to HIV. But some believe that a side effect of the transplant may actually have been at least partly responsible for wiping out the virus in his body.

Known as graft-versus-host disease, it is caused by immune cells from the donor attacking those of the recipient. Brown's bone marrow transplant triggered this, causing his own immune cells —and the HIV they contained— to be killed.

"Six more people with HIV and cancer who have been treated in the same way as Brown now seem to have no trace of the virus in their system", says Javier Martínez-Picado from IrsiCaixa AIDS Research Institute in Barcelona, Spain. Only one of the six received bone marrow from a person with the CCR5 mutation —however, all six developed graft-versus-host disease.

"We won't know if the six people have completely cleared their bodies of HIV until they stop taking their anti-HIV drugs. That may happen for the first person within the next year", says Martínez-Picado.

"If the theory is right, that would be tremendous", says Annemarie Wensing of the University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, who presented data on two of the six at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases in Vienna last week. All HIV tests on the six have been negative for more than two years.

A different approach for treating HIV has recently shown promise. Known as "kick and kill", this treatment wakes up dormant virus that has been hiding in a person's cells and then targets it. This has enabled five people to stop taking anti-HIV drugs, but the virus is still present in some of their immune cells.

That's not so for Brown or the six newer cases, who come from various countries.

If graft-versus-host disease does turn out to wipe out HIV, doctors would be reluctant to deliberately provoke this potentially fatal condition in people. An international consortium of researchers, including Wensing and Martínez-Picado, has been following 23 people with HIV who received bone marrow transplants to treat cancer. So far, about half have died —either from the transplant, or their cancer.

Current anti-HIV drugs mean that people in rich countries can largely keep HIV under control, so inciting graft-versus-host disease wouldn't be a desirable option.

"But the consortium is studying the transplant recipients to learn more about where HIV hides. This should help develop a cure without the need for a bone marrow transplant", says Martínez-Picado.

Read original article by Clare Wilson here:

New Scientist.com

Timothy Brown

Image from eecaac2018.org

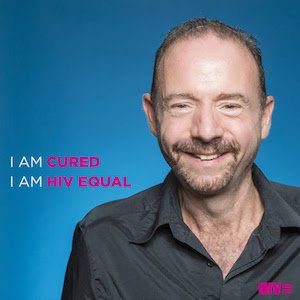

Bone marrow

Image from Medical News Today.

"Some believe that a side effect of the bone marrow transplant killed off the virus in the body"

CCR5 gene

Image from crdd.osdd.net.

BREAKING NEWS!!

UK man becomes second person cured of HIV after 30 months virus-free

March 10, 2020

A man in London appears to be the second person ever cured of HIV, his doctors said.

The man —whose case was first announced a year ago— has now been HIV-free for 30 months without the need for antiviral medications, according to a new report published Tuesday (March 10) in the journal The Lancet HIV. Continue reading...